Roan

„Whatever makes you angry, take the anger and chuck it away.

You don’t have to be angry.

Remain silent.

The forefathers of our home used to say: when something bad befalls you and you stay silent, then nine good things come to you.

If you remain silent, then nine good things come to you.“

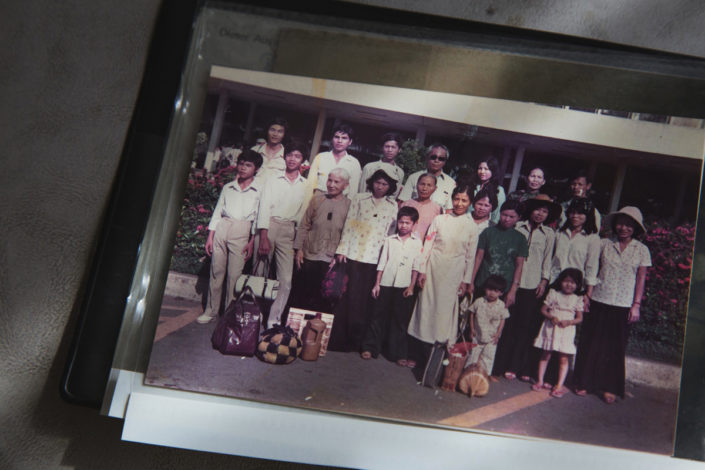

Mrs. Roan was the oldest sister among seven brothers. Even if she was far too young, her parents placed great responsibility on her. Besides taking care of her younger siblings, the usual chores were cleaning, cooking, doing the laundry and feeding chickens. Mrs. Roan attended school until the 3rd grade, only to learn how to read and to write. When she turned 18 years old, her parents arranged a marriage. She moved out from her small and spare cabin to a grand mansion. As a young wife and mother, Mrs. Roan had to serve her wealthy parents-in-law and her husband, while raising her own children. In the 1950s, with the uprise of the militant Viet-Cong in North Vietnam, her family was politically persecuted and forced to leave their home behind. They found shelter in the outskirts of South Vietnam. The family survived with home grown vegetables, which she used to sell everyday. Her husband, who became an alcoholic, would not support her. Only a few years later he died – leaving Mrs. Roan and their eight children behind.

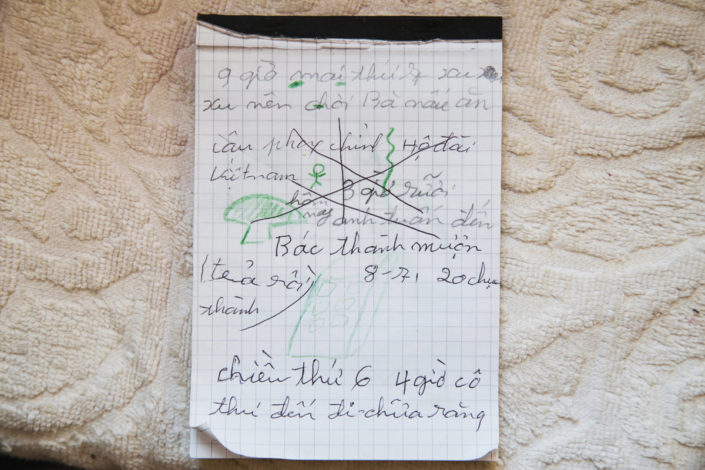

Mrs. Roan and her children migrated from Vietnam in 1984. They found asylum in Germany. While it’s been over 30 years, she does not speak a word of German. To this day, she regrets quitting language school very much. She could rely on her children to help her through daily struggles. Now, they don’t have much time for their mother anymore. The loneliness has become normal. However, Mrs. Roan is now 83 years old. Her xenophobic upstairs neighbour harrasses her. She needs to be taken care of more and more. She has trouble managing daily chores and starts to forget ordinary things. Sometimes, she even forgets the names of her grandchildren.

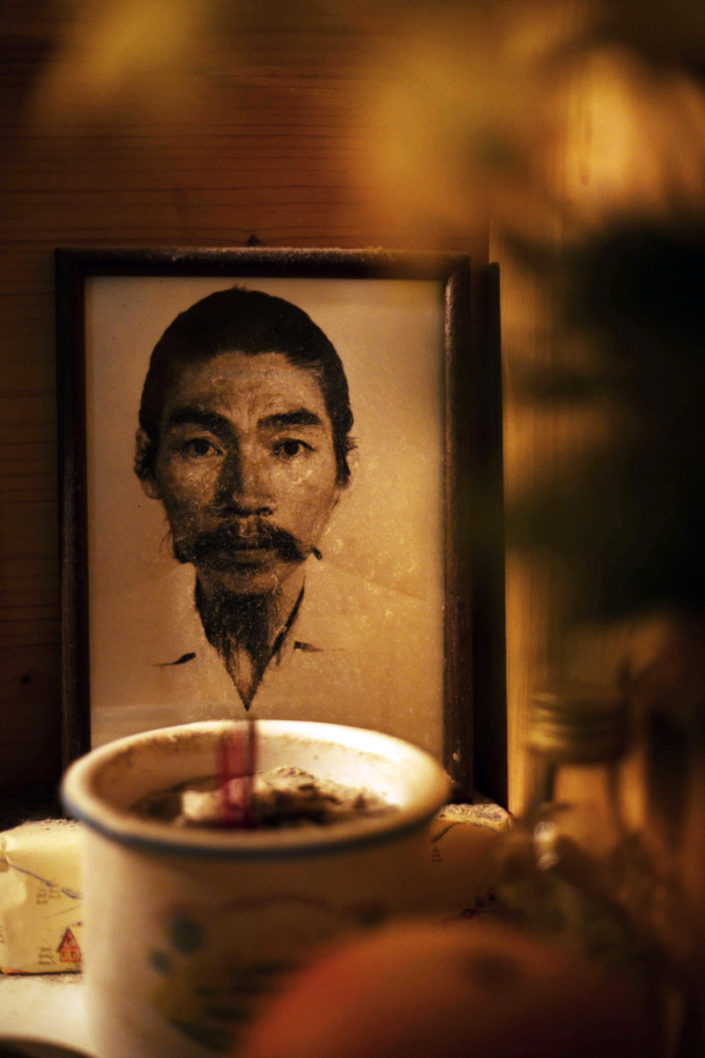

Unfortunately their sons don’t have enough place for Roan and for the six foot altar, which she is cultivating every single day as Buddhist. Only her daughter lives in a house big enough for her mother, but that’s out of the question. When a daughter gets married, she doesn’t belong to the family anymore. Paradoxically, she’s the one mostly taking care of her mother.

Her children hardly talk to each other anymore. It seems that after thirty years in exile the family is falling apart. That would be Mrs. Roan’s greatest fear because to her family is more important than her own happiness. She imposes boundaries and duties on herself barely to hold everything together. She is the core of the family, yet the loneliest.

Her case is individual, but it reflects on many other Vietnamese refugees in Germany. The lives they left behind, the problems they faced and the generations that drift apart.